UFFP met reporter and photographer Martin Middlebrook, at the 20th edition of ST- Art in Strasburg, last november 2015.

It was like « love at first sight » when we saw his work. It was not about the beauty of the shots only but we were touched by the many moving stories behind them.

We could feel that and of course, meeting « the eye » behind the shots, helps us a lot as well !

UFFP unveils you, who Martin Middlebrook is.

We chose to keep the interview in english and not translate it in french, to remain as faithfull as possible to the original text.

Martin Middlebrook had many lives before coming to Paris…

Born in Lincoln in 1967, Martin Middlebrook has lived all over the world. The son of military parents, he was educated at the Royal Grammar School Worcester, and Bournemouth and Poole College of Art and Design. Prior to working as a photographer, he ran his own design business. His images have been used to illustrate a number of international causes including famine in Ethiopia, the reconstruction of post-conflict Afghanistan and the threats faced by Tigers in India’s national parks. He has worked for a number of clients including the BBC, GCHQ and the United Nations.

Interview with UFFP

Tell us about your background, from publicity advertorial work to reporter in the field?

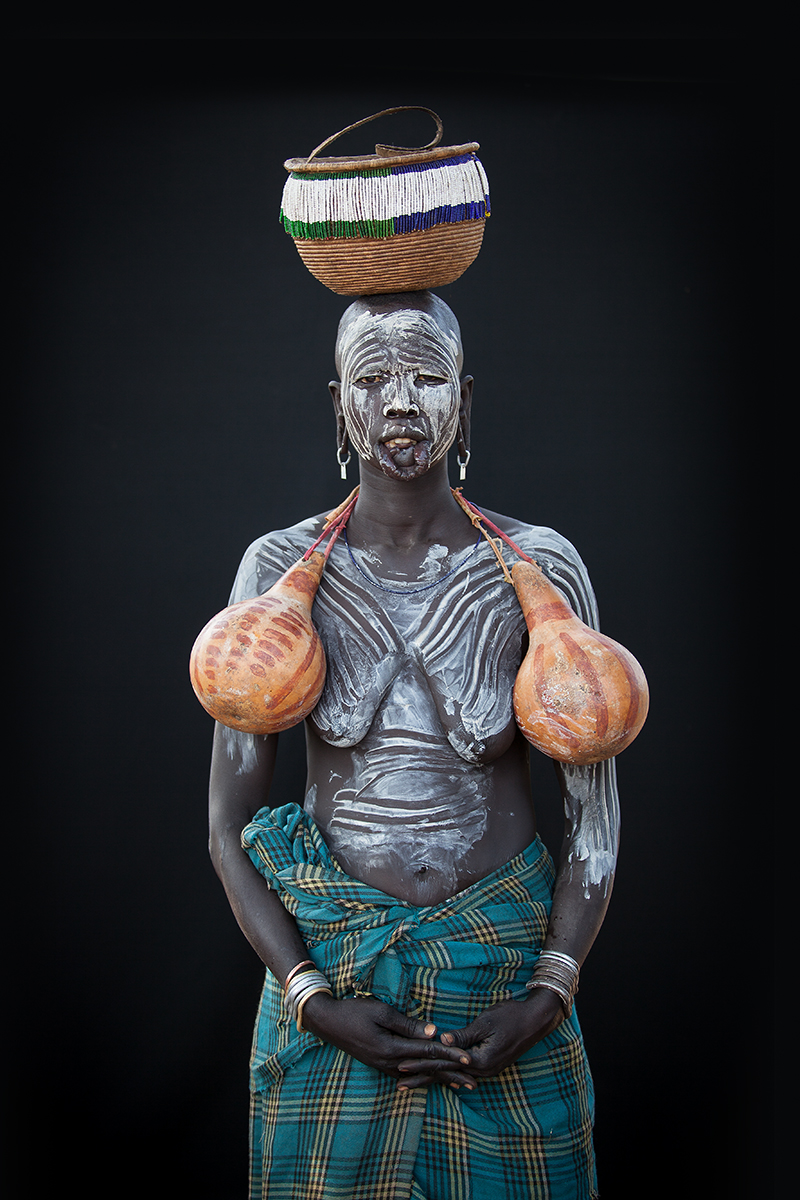

Mursi Tribe – Lower Omo Valley, Ethiopia, November 2014. I used a black background to detach the subject from their environment – a mechanism that I hoped would connect us more directly with these extraordinary people. © Martin Middlebrook | All Rights Reserved

I actually trained as a wildlife artist, before running my own graphic design business in the UK. I had my first camera when I was 13, and started to develop my own work in a darkroom from the age of 16. When I had my design business we increasingly employed creative concepts that included photography, which I would do myself. In time, my love for photography became too strong and I went full time.

Mursi Tribe – Lower Omo Valley, Ethiopia, November 2014. The Lower Omo Valley is home to 14 distinct tribes, each with their own dialect, decorative style and traditions. © Martin Middlebrook | All Rights Reserved

I did a lot of conceptual/lifestyle images for brands, plus PR and events work – what I would call ‘bread and butter’ work – but it taught me so much. In 2001 I was in southern Ethiopia and shot some images that ended up being used internally by the British Government – the result being that they committed considerable aid to famine relief in the area. It was my first taste of the power of images for a humanitarian need. And then in 2003 I was invited to Afghanistan to undertake a project for the United Nations Development Programme – my first real experience of photojournalism.

Which countries have you visited? What kind of reporting work did you achieve?

Mursi Tribe – Lower Omo Valley, Ethiopia, November 2014. This image is always misjudged. This is not a war, or a child soldier, and neither is it aggressive. The 14 tribes of the Omo Valley used to carry spears to protect their livestock from attack by natural predators. The AK-47 has merely replaced the spear in some villages. © Martin Middlebrook | All Rights Reserved

I have worked in Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Lebanon, India and Nepal. In January 2016 I begin a project on the Ivory Trade that will see me visit Kenya, Botswana, Ethiopia, Gabon, China and the US.

The main focus of my work has been Afghanistan. I revisited it in 2009, and in 2010 I was commissioned the Government of Afghanistan to produce a humanitarian piece for the Kabul International Conference. I moved to Kabul in 2011, and spent a year living and travelling the country.

Kabul – Afghanistan, November 2011. A child cast a shadow, somehow larger than life. I have always looked for visual metaphors in my photographs that better express the truth of the human condition. © Martin Middlebrook | All Rights Reserved

My focus in Afghanistan was to create a portrait of the largely unseen side of the conflict there. It was a human piece, and although I went on ‘embed’ with the military, and saw my fair share of some of the terrible consequences of war, it’s not something that I went looking for. I believe in the true human condition, and I have always had a philosophy that people are better than we allow, we should represent them more honestly in our images.

Kabul – Afghanistan, June 2009. Children play in the streets of Carte Seh, as the heat of a hot summers day creates a mini tornado. Afghanistan is the country I feel closest too. I couldn’t say it’s the country I love the most – but somehow its people, history and culture get inside of you and never leave. © Martin Middlebrook | All Rights Reserved

The work I created there – ‘Afghanistan – From the Other Side’ – went on to exhibit at the British Museum in London, appeared on Arte TV’s landmark series on the 10 years of conflict in Afghanistan, as well as being published around the world.

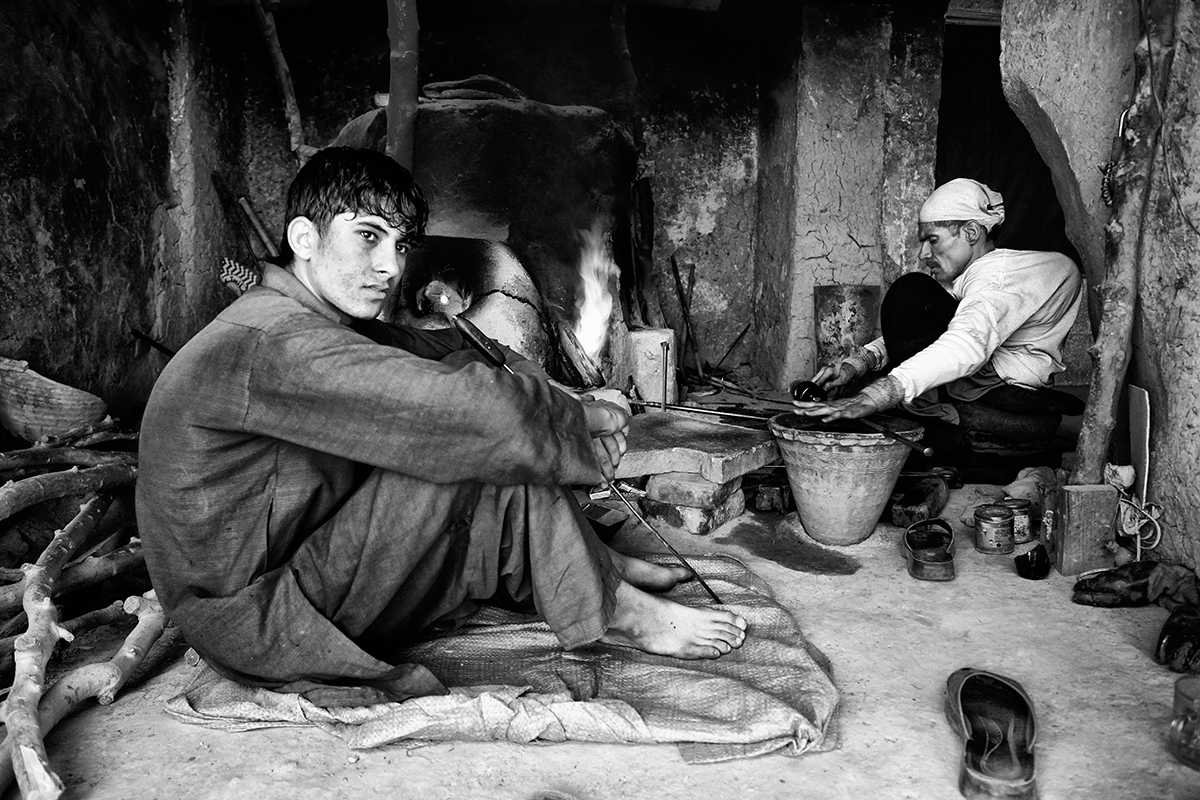

Herat – Afghanistan, June 2010. Glassblowers swelter in the midday heat, in tolerant Western Afghanistan. I spent a year of my life travelling a country that until the Soviet invasion of 1979, had barely changed in 5000 years. © Martin Middlebrook | All Rights Reserved

I recently completed another piece of work for Arte TV for their five part series on refugees, during which Arte broadcast a documentary about my work. We photographed and filmed Bhutanese refugees that live in camps in eastern Nepal. My work, along with the other contributors will be published in a book in 2016, as well as exhibiting in Strasbourg. It was an extraordinary honour to be part of a project that could not be more timely, and more urgent. The chance to represent people honestly and to hopefully be a tiny part of a process that engages in change is a key part of why I do this.

How did it influence your art and vision of the world?

I have always held very strong views, which are somewhat anti-establishment. Everything I have witnessed in my time in the field has merely confirmed what I have always suspected deep inside. I have been fortunate, that in addition to my photographic assignments, I have written over 100 articles about photography. I have always used these platforms as an opportunity to try and illicit some change in the way that images are envisioned, assigned, and finally broadcast – through whatever specific media.

I know that my views have not made me particularly popular with some, but I am probably too old to care. I have always valued the experiential aspect of being a photographer, the chance to meet amazing people, to briefly be part of their world and to tell their story. That is a privilege that few people have. What it teaches you is that you can see and represent the world in many different ways – and each is a kind of truth – but there is always more than one truth. I have chosen to try to convey a deeply positive representation of humanity, because I do believe that the vast majority of people are good. And I do believe that in doing so we have the greatest chance of creating positive change.

A couple of years ago I received a letter from a Syrian lady in which she said; “As the Dalai Lama and Howard Cutler discuss in the ‘Art of Happiness in a Troubled World’, it is the way we think that we need to look at if we are to stop the violence. Make people feel good about being human and make them relate to ‘the others’.”

I truly believe this; that we need to change the way we think about ‘the others’, and images are a fundamental part of that. It has undoubtedly determined my style, my approach and ultimately the finished picture. It could be viewed as a little nostalgic, that maybe my images are overly human – but for me it’s a better starting point than simply seeking out ‘darkness’.

You seek for a certain kind of honesty towards visualising reality? It is a certain kind of criticism towards how medias use images?

I have strong views about this – I have had many discussions with picture agencies, wire services, media organisations – where we agree to disagree. My personal social media stream is mostly depressing; I can barely find the strength to look at Twitter most days because very little of what I am being told is changing the way we think. There is no doubting that the stories are true, but this dependency on representing just one side of a conflict for example, is at best turning us off, at the very worst, it is dehumanising us.

It’s hard to remember a time when the world was fighting crisis on so many different fronts. Given that this desire to show an exploitative view of the world has been part of our ‘make up’ for a good few years now, and given that the world is sliding in the wrong direction, then doesn’t it make sense for the media to more equally represent different truths? I say this respectfully to photographers and journalists who risk their lives every day to uncover and deliver the relentless tragedy of so many suffering communities. But all the evidence suggest that how we are representing the world, is not working. So perhaps we should review that?

I start a project on the illegal ivory trade in January, and the whole philosophy, both mine and the clients, is to shift the ‘value system’, to demystify ivory. I am sure we will end up photographing dead elephants; its inevitable. But it will not be central to the story we are telling. It will be interesting to see how the world’s media pick up on our approach.

Your experience in Afghanistan can you tell us about it? What did you learn? How do you see western implications today in these regions?

It’s always complex to honestly relate your understanding of something. If I have learned one thing, it is that being too honest can close down access – and if you want to continue to represent something, access is important. However, its no great mystery that where we are right now, the rise of fundamentalism, the refugee crisis, the tragedy of the unraveling of the Middle East and parts of Asia, are as much a result of western agitation, greedy proxy interests, and to some degree, a thirsty media. It’s very easy to chart the start of this process, and outlining that here will add nothing to the argument. You can read about it everywhere.

I think the key to solving the issue are threefold. Firstly education – education is perhaps the biggest game-changer in the ‘New Great Game’, and presently it is in the wrong hands, globally. And education requires a generational shift – something that is difficult to achieve in a five-year electoral cycle. Second, we need to have a legitimate and fair process of accountability. It is extraordinary to me how the West is able to conduct itself to achieve its aims, without any recourse to the law. Why should the International Criminal Court only prosecute those from so called ‘developing countries’? If we showed the Muslim community that we were serious about accountability, it might perhaps be the beginning of a change in the way we, in the West, are perceived. There is no justification for terrorism, but how can we denounce, when we ourselves prosecute often illegitimate war, and then don’t hold ourselves accountable. And thirdly, we need a media that is less tied to institutional process, less compelled politically.

The media argument is a difficult one, because the world is full of passionate people who fight day and night with a pen and a camera to change the world for the better – what we need is balance from content platforms.

Tell us now about your work in the OMO valley in Ethiopia? Why did you choose this region?

I remember visiting the Addis Ababa Museum in 2001, and looking at the skull of ‘Lucy’ – at the time, our oldest known ancestor. Ethiopia was the seat of humanity, and Omo Valley, and Lake Turkana in Southern Ethiopia and Northern Kenya have unearthed the greatest evidence so far, that this is where you and I came from.

Back in 2001, I couldn’t get access to Omo, and I was not a competent enough photographer to do it justice. So I have spent much of the last 14 years trying to find the time to go back and chronicle the lives of the extraordinary tribes that live there. The style I chose was partly empathetic, and partly selfish. I wanted to strip everything back so that the subject was not attached to a specific environment. The way I see it is this – you could take these pictures on the streets of any Western city by simply adding the decorative aspect to people here – and in most cases you couldn’t tell the difference. It was an important way for me to say that we are all the same.

The approach was partly this, and partly to dignify these amazing people, who until recently were relatively untouched. Their predicament is desperately concerning for many reasons – I hope that these images can be useful in showing the world that we need to consider our treatment of different ethnic communities as we progress with our plans – because respecting our past, our provenance, should teach us to respect our futures.

Tell us about your project HUMANS?

HUMANS was just a hidden philosophy. Every thing I have ever done has human beings at the heart of it – and it was only in redoing my website a year ago, re-editing portfolios and so on, that I could fully see that. The piece we will do on Ivory will be as much about Humans as it is about elephants – in fact it will be more about humans, because elephants aren’t killing elephants, humans are doing that.

I have a personal project that I started recently – a series of ‘seascapes’ – abstract fine art pieces, with not a single person in them. But in fact it is all about people, because I recently bought a house in Brittany and wanted to try and understand why people from the area have such a deep connection, an affinity with the sea. It seems to be in their DNA. So by literally looking at the ocean day after day, feeling its rhythm, understanding its tides and energy, I have come to appreciate more completely how important the sea is to them. Photography is the perfect mechanism for me to understand people.

I always think there are three people in a photograph – the subject, the photographer, and most importantly, the viewer. And we are all just people.

You are British but based in Paris, and you have a gallery here?

I came here by chance. I wanted a few weeks away from Afghanistan – I wanted some peace. And I just ended up meeting so many wonderful people, at a certain moment in my life when that’s what I needed the most – and I stayed. So it became a home for me, and a base from which I travel. I am represented here by a private gallery called Mondain (mondain.paris@gmail.com).

You just came back from Strasbourg and the Re Start Art Trade fair, your impressions?

Strasbourg Art Fair confirmed to me what I think I knew already – that the nature of how we use technology to convey our personal ideas is changing our output. From a photographic point of view, very little of what was exhibited was ‘straight’ photography, its what I would call ‘photographic art’. That makes it no less legitimate, in fact its very often far more compelling; but I think we have to rethink some definitions. I trained as an artist before, and what I see is people using photography as a base to create art – because in simple terms, they can’t actually paint. There are some wonderful conceptual ideas out there – work that would not have been possible before the likes of Photoshop and so on – but I am not sure we should call it photography, and the creators ‘photographers’.

This may seem pedantic but my reasoning is as follows. People believe that a photograph is true, and that is very important – we must trust it or it devalues the medium. Experience tells me that people are often ignorant, and if you tell someone it’s a photograph, they will believe you without questioning it. That leaves the consumer open to being deceived. If we just looked at our definitions, then we can avoid the tragic possibility that the legitimacy of photography being used as an instrument of honest representation, will be lost forever.

There was however much compelling and fascinating work to be seen – and that is a wonderful thing at this time. I felt heartened.

Tbank you Martin !